Dorothée Pullinger, nowadays celebrated for her pioneering work as an engineer, car producer and entrepreneur, has generally been more associated with the Dumfries area of Scotland where she worked after the First World War before moving to London and then Guernsey.

However, to understand how she came to be so successful in those later moves in her careers, it is helpful to look back to her younger years. It is no coincidence that the word for vocational training in some European languages is “Formation”. I would think that those of us ‘of a certain age’ can all look back to our teens and early twenties and recognise how formative those years were on our working lives and careers. And so it would have been for this remarkable young woman, which is why I want to talk a bit about her life in Paisley at the start of the twentieth century.

Dorothee Aurelie Marianne Pullinger was born on 13 January 1894, at St Aubin, Seine-Maritime, Haute-Normandie, Her parents were the English car designer Thomas Charles Willis Pullinger (1867–1945) and Frenchwoman Aurélie Berenice Sitwell (1871–1956). Between the time of her birth and the eventual move by the family to the UK in about 1902, her father worked for a number of early car makers in France: Darracq, Superbie & Co, Teste & Moret, before being recruited by Sunbeams car and cycle company in Wolverhampton. Initially only speaking French when the family arrived in England, Dorothee was sent to Loughborough High School. In 1904 her father moved to Humber’s car factory, in Beeston, and then in 1907 to Beardmores in Paisley.

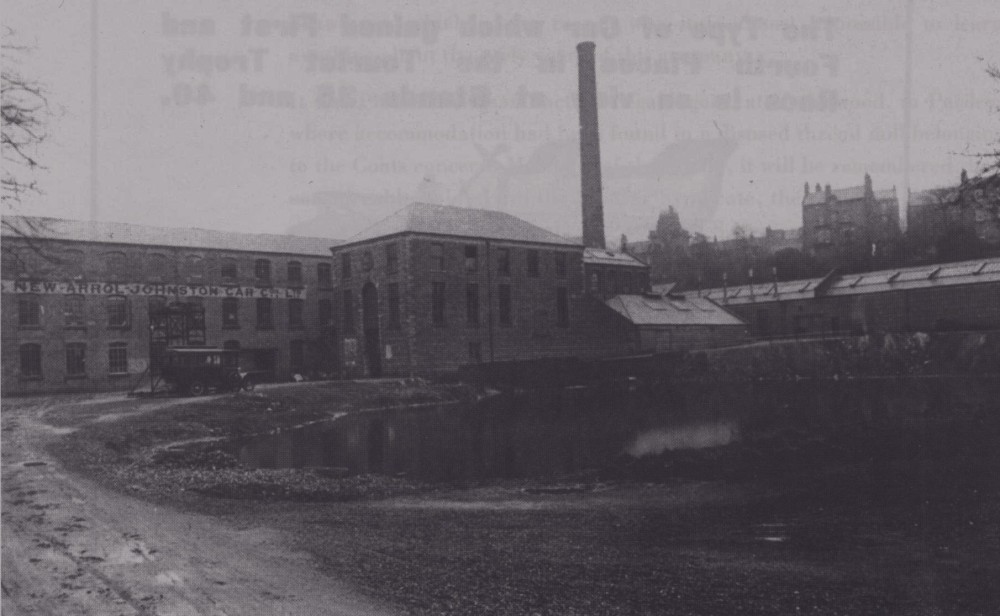

William Beardmore had invited him to take on a car factory in his group of companies, Arrol-Johnstons, at Underwood in Paisley. Thomas Pullinger had something of a reputation as a manager who could ‘break the unions’ and Beardmore may have wanted him for this reason. The factory had been losing money and Beardmore was not willing to invest further but if Thomas would take the managership on that basis he could get 1/8th of the shares, paid for out of any profits. He had to find the first week’s wages for the workers by retrieving and selling scrap from the factory dump in the pond nearby.

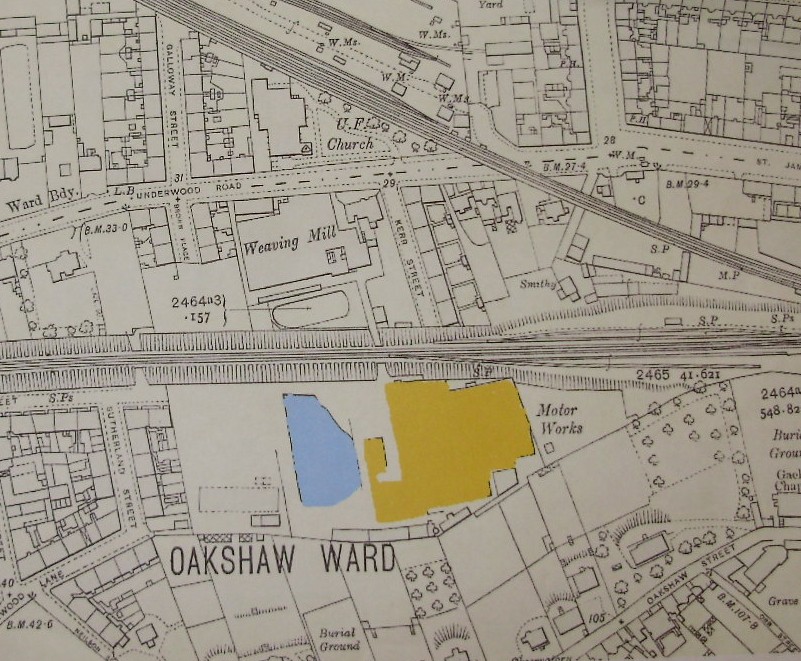

The Underwood factory, although it had a painted sign along its length declaring it to be the “New Arrol-Johnstons” car factory was in fact already pretty old. It was originally built as one of the many Coats’ thread mills in a complex of several smaller older mills in the Underwood area, and lay between the railway to the south of Underwood Road and the steep hill which still has the Coats’ Observatory on its top. Built in the 1780s and largely rebuilt in the 1860s, it was already looking very shabby in 1908. The main building was three storeys with an attic, in a 3-by-14-bay structure, with 7- and 8-bay blocks of north-light weaving sheds at the rear. Part of the main building had been built for one of the first Boulton and Watt steam engines, then revolutionising British industry. There had been numerous small thread and weaving mills in the Underwood area from the start of Paisley’s textile boom and the requirement for spinning in particular to keep the threads damp meant that there were many artificial ponds dug in the area. A smaller pond on the north side of Underwood Road survived as a municipal amenity well into the twentieth century. However a larger pond beside the Arrol-Johnston factory was still in place in 1908 and can be seen in photos of the factory as looking like derelict land with standing water and rubbish. It is presumably this rubbish that constituted the scrap metal etc that Thomas had to arrange to recycle in order to ease the cash flow when he took on running the factory.

Everything of the Underwood factory is gone now, replaced with a small housing estate. There is a length of old brick wall at the rear of one of the houses which may be all that remains of the retaining wall behind the factory at the foot of the hill.

This shabby old factory is almost certainly where Dorothee started her training to become an engineer when she left school at 17 in 1909. Her family say that Thomas was at first highly resistant to his daughter entering a male environment and doing engineering, then seen by all as not for women at all. He probably expected her to remain at home to help her mother with the many younger siblings, until she married. To please him she took a secretarial course which, while no doubt useful in her later careers, did not suit the young Dorothee’s ambitions and she returned from the course demanding that she now be allowed to follow her preference. Thomas agreed and she started work in the drawing office in about 1910. In this respect she would be one of the last generation to take this old-fashioned route into professional engineering.

Already, even at this early date, a number of women had been taking science-based degrees at the Scottish universities but mainly because they wished to become medical doctors. It would not be long, however, before Elizabeth Georgeson gained a BSc in Engineering from the University of Edinburgh (1919), probably the first woman to do so. Men aiming for an engineering career at this time would probably mostly have gained a degree and then joined an engineering firm as a junior. The old way, of being a pupil to a senior practicing engineer, similar to an articled clerk in a lawyer’s office, or of using parental influence to find a position through patronage, was dying out by now. However, for a woman like Dorothee, steeped in the environment of engineering from birth and presumably at least witnessing engineering conversations when her father’s colleagues visited the house, making use of her father’s connections and status was a reasonable choice at the time. She would not be the only woman of this period to do so. Victoria Drummond (1894-1978), the pioneering female marine engineer, was almost exactly Dorothee’s contemporary in Scotland and made use of her own aristocratic family’s connections to get the practical training in workshops and shipyards she needed in order to become the first woman to become a ship’s engineering officer. At the other end of the country, Cleone de Heveningham Benest (1880-1963), motor engineer and metallurgist, on the Isle of Wight made use of her family’s wealth to set up her own workshops and buy expensive cars as well as connections in the engineering world’s aristocrats to create an engineering career for herself.

Whilst, from the social viewpoint of today, we can look at these three women as having come from various degrees of considerable advantage and privilege, we should still recognise that these advantages would not in and of themselves have been sufficient. At the dawn of the twentieth century life was only very slowly opening up for middle class women but only those with ability and considerable grit and determination could make it into the harshly male engineering environment, regardless of advantage or connections. As Drummond was to discover the hard way, the key test of a professional engineer in British industry then was, perhaps still is, how well one could manage the ‘men’ – those who did the unskilled, labouring, semiskilled tasks and skilled craft work on the factory floor, or down the ship’s engineroom’s ‘pit’.

Everything about the world they wanted to enter would have been against them. The necessary education was difficult to get, since by no means all schools for middle class girls taught any science at all. The essential first job was difficult to get unless you had contacts, and indeed for many young women this remains a barrier even today in such areas as the skilled construction trades. Prior to the industrial upheavals of the first world war the only industrial settings in which significant numbers of women worked were in the textile mills and the industrial laundries and in those industries they were semi-skilled machine operators rather than engineers. Men looked after the machinery and, by and large, held the managerial posts. The wholly male environment of the manufacturing workshop was not one where women would feel welcome even it they could get a sympathetic proprietor to offer them a start. Not only were the trades unions highly protective of their trades, in emulation of the medieval guilds, many works had their own freemasonry lodges and other social groups which would have been explicitly anti-feminist. Until the 1920s scarcely any of the local or national professional and scientific bodies admitted women to their lectures, let alone membership, so that the networking normal to men of all social classes would also have been prohibited to women seeking to become engineers. Men controlled all the entry points and mostly kept them locked against women at this time, hence the importance of Dorothee’s father’s high-status position in getting her the start she needed.

Bearing in mind that Dorothee was starting out before the social revolution of the first world war, even appropriately female, but practical, clothing would have been an issue, even for someone aiming not at the shopfloor but at the ‘white collar’ level in the drawing office. The bloomers which some very daring young Edwardian young women chose to wear when out bicycling were considered indecent in many parts of polite society, to say nothing of the opinions of the more conservatively religious groups which abounded in Scotland at the time. Drummond was forced by her family to wait for her ‘majority’ at the age of 21 before she could choose her own way in life and start training in a garage, but by that time WW1 was underway and thousands of young women were in coveralls in factories. We do not know what Dorothee wore to work but her clothes would have needed to be dark, tough-wearing skirts that could stand getting filthy around the hems and being frequently scrubbed clean.

Whilst we know that Dorothee and her father were both living in Scotland in 1909, it is not clear whether the rest of the family had moved to Scotland at this point. However, in 1912, Thomas’ mother, Marianne Pullinger (nee Willis), died at 54 High Street, Paisley. That house number is slightly confusing to anyone looking for the location today, because the council changed all the numbering in the High Street (and many other Paisley streets too) in 1923 and what had been 54 is the location then known as 91.

Local historians believe that their home would have been one of a pair of old terrace houses between a row of shops and the Coates Memorial building, all now long gone. The houses seem to have been in the flat-fronted style each with a set of steps leading up to the neighbouring front doors above street level. They were probably from the Georgian period and survived the demolition of the Coates building when it was replaced with an art deco ABC cinema. The entire block was later demolished to build part of the Paisley Technical College where the new University of the West of Scotland building is now, opposite the Paisley Museum. This house was within short walking distance of the Underwood factory. Thomas’ mother is buried in Paisley’s ‘necropolis’, Woodside Cemetery, said to have been designed to emulate the famous Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris, and is also only a slightly longer walk away eastwards along the High Street.

Whilst Thomas (TC) Pullinger was listed in the Paisley and District Directory from 1910-1914 as being the manager at the Underwood factory and living at Swinlees farm just outside Dalry, it is not clear where Dorothee or her grandmother were living as neither is mentioned in the directory. However, letters from Dorothee to friends and family in the period 1910-16 were addressed as having come from Swinlees. Number 54 High Street seems to have had an annually-changing cast of doctors or dentists living there, but it was not their consulting premises and no one else is listed as living in what was a substantial house. Presumably, as with later telephone directories, only the principal tenant of each address was listed in the Directory. Marianne Pullinger was by now very elderly and perhaps infirm so there might reason to suppose that Thomas did not think that the isolated farmstead in the Ayrshire countryside was a suitable place to leave an old lady alone all day, who might need medical attention. There is no reason to surmise that number 54 was some kind of informal nursing home and it would seem unreasonable and unkind to ship his elderly mother from London to Paisley, where she would have known no one and then park her in a lodging house alone. We can never know for certain now, but I think it is possible that Marianne and her eldest granddaughter, Dorothee, might have lodged together at number 54 at ;east for a period. The house would only have about 10-15 minutes walk from the Underwood factory for Dorothee to get to work each day. I like to think she may have lived where the University of the West of Scotland now stands, educating today’s young engineers.

Dorothee’s induction into the world of engineering was via the drawing office in the Underwood factory. Even this early in the twentieth century it was not unheard of for young women to work in the drawing offices of large engineering works, but usually in the lowly role of Tracer. Henry Dubs is said to have preferred to recruit women, rather than young men, for this work in his North British Locomotive works in Glasgow. These tracers were essentially human photocopiers: they literally traced other drawings, usually the working copies on which the senior designers (men) had made so many alterations that a clean version was needed. The work was exacting and routine and these women Tracers had little prospect of promotion to more responsible work. The day was spent standing at a sloping board working with pencil and paper, indian-ink dipping-pens, rulers, scale-rules, french curves, compasses and dividers, to produce a perfect drawing from which components could be made and assembled. As the daughter of the managing director, obviously Dorothee was in a privileged position and her trainee role would probably have seen her spend some months getting to grips with this totally new skill, one unknown to today’s young engineers using computers for everything.

Thomas was not impressed with the Underwood thread mill buildings in which he had to get cars built and in 1912 he traveled to the USA to observe car factory design and the mass production methods in Detroit. On his return, he persuaded William Beardmore to part-finance a completely new factory at Heathhall near Dumfries and a few years later the whole family moved there, leaving Paisley behind them.

These had been formative years in Paisley for Dorothee and prosperous ones for her father, Thomas. The move to Dumfries was the next great chapter in their stories.

Just found your web site and look forward to reading more. I am a volunteer guide at Riverside Museum and a great admirer of Dorothee Pullinger. We have a Galloway, or rather did until a couple of weeks ago when it disappeared from display. Apparently it is to be the centre piece of a new stand alone display featuring Dorothee and I am looking forward to seeing it in in due course. Apparently there are only two Galloways left in Scotland, the museum one and another at the Motor Museum at

Myreton near North Berwick. Unfortunately it was locked away in a barn when I visited some time ago.

I noticed that there is a tantalising photograph of the Galloway owned by the family in Guernsey. Is it possible to see the whole car rather than just the radiator? I would love to have the opportunity to open up my tool box and get our car running so that visitors can hear it see it and even smell it, but I guess that will never happen which is a shame. I do have a presentation with lots of pictures on my tablet which covers the history of the Scottish car industry, and a lot more besides. I can be found at Riverside all day most Saturdays if anyone wishes to look me up. A picture is worth a thousand words. The museum is free and well worth a visit.

LikeLike

Robert,

Thanks for your comments. To the best of my knowledge there are 4 Galloways in Scotland. The ones in the Riverside and Myreton museums and two others in private ownership one near Edinburgh and another which I have not seen but which is in Aberdeenshire. The latter two I gather are both roadworthy as is the Guernsey one.

LikeLike